Events

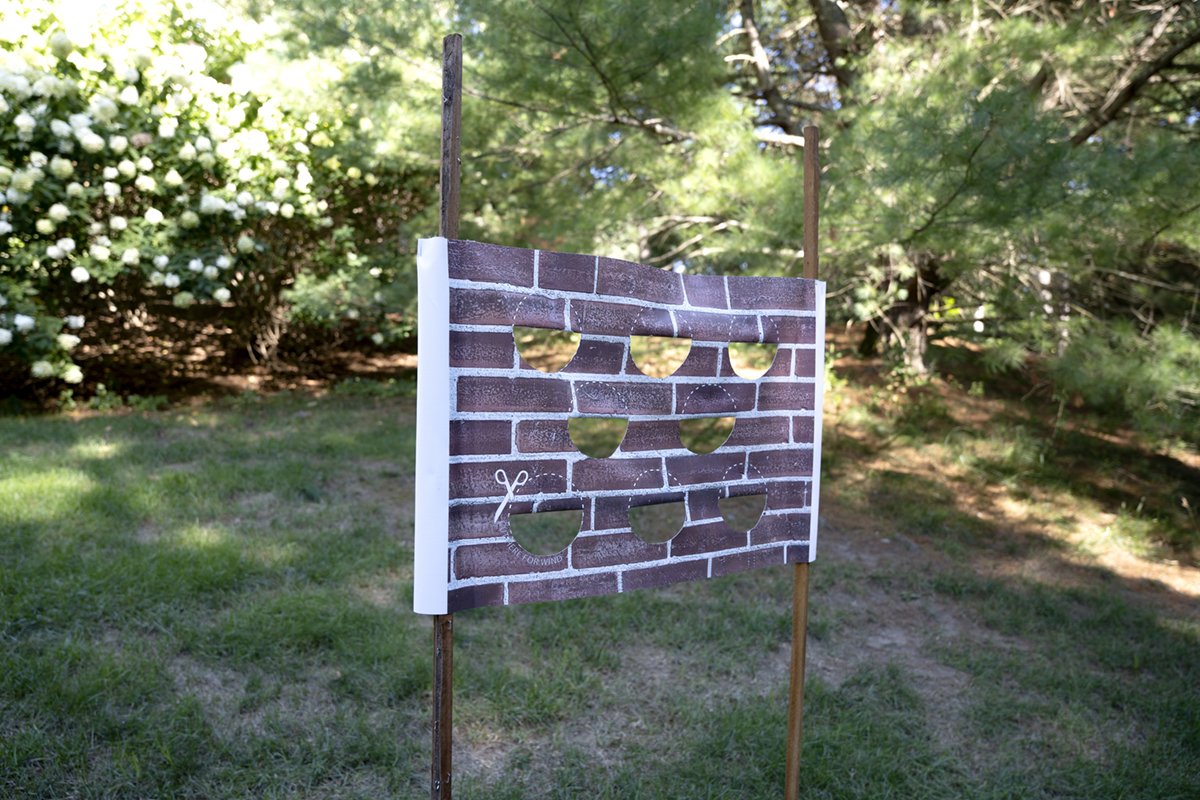

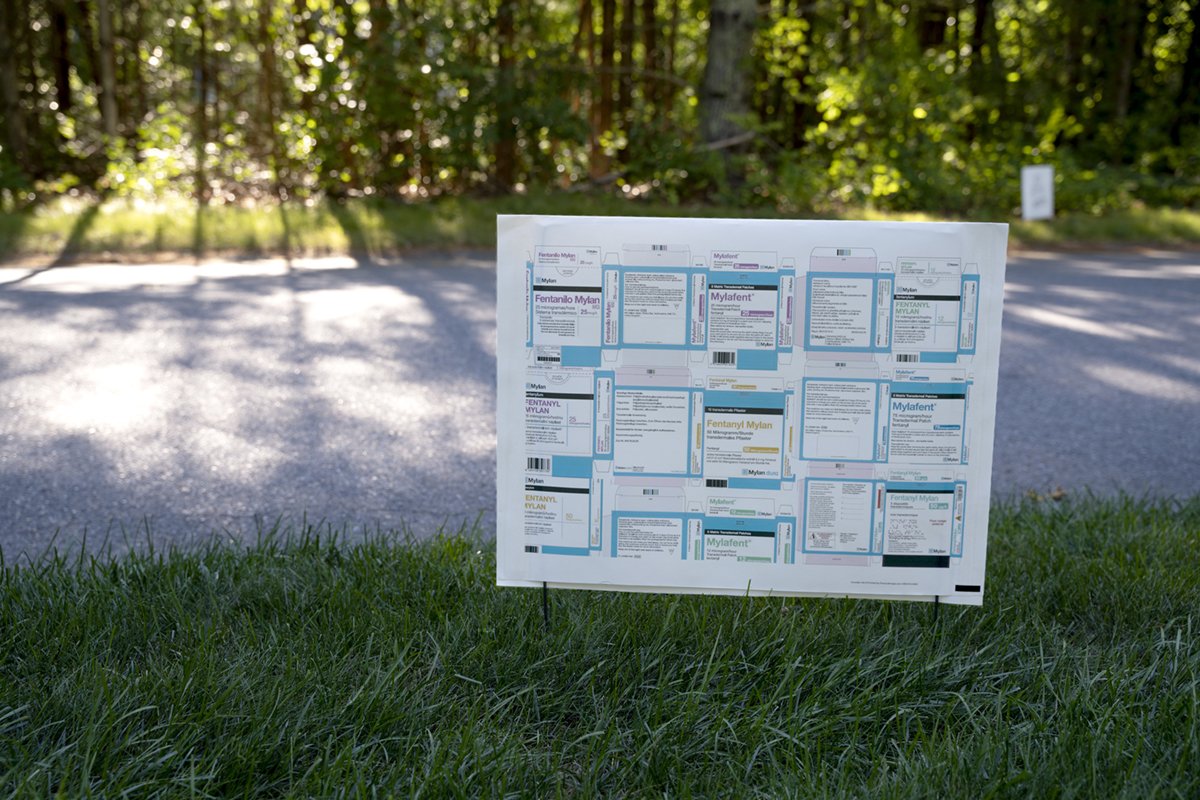

**CURB ALERT** for Cosmos Carl

a **CURB ALERT** posting on Boston Metro West Craigslist, informing you of an exhibition of artist-made lawn signs, one day only, in suburban Massachusetts. First come, first served, no calls please, in perfect condition, what you see is what you get, all parts included, it’s on the curb – just come and see it.

The link went live on Cosmos Carl on Friday, September 2nd at 17:00 CET and will remain in their archive for perpetuity or until Craigslist removes the post.

with works by:

Alcide Breux

Andrew Holmquist

Anika Todd

Backyard Invasives Project (Dan & Annelies Kamen)

Elena Ailes

Erin Woodbrey

Jesse Malmed

Jessica Campbell

Kelly Lloyd

LTE (Kate Conlon & Boyang Hou)

María Luisa Sanin Pena

Soline Krug

Unyimeabasi Udoh

hosted & posted by Annelies Kamen

CRYBABY FEE FUND

If you’re a BIPOC or QTBIPOC artist/writer and you’re applying for a residency, grant, educational program, exhibition or funding opportunity that requires an application fee, send an email to crybabyberlin@gmail.com and we’ll send you 💰 to fully or partially cover that fee. We’ll keep paying fees until our fund of €3000 is exhausted. Please share, tell your friends, get folks paid.

HELP (Is anyone an artist?)

a new performance by Kelly Lloyd with Elizabeth Ravn and Annelie Andre

organized by Annelies Kamen for Crybaby

June 13th, 2019

6:00-6:30pm

beginning at:

Genthiner Str. 36

10785 Berlin

Crybaby is happy to present this performance as part of When The Hunger Starts - Project Space Festival Berlin 2019 kindly supported by the Berlin Senate Department for Culture and Europe.

When talking about the relative importance or value of art, why is art set against the things we need to survive? Because you can't eat a painting, does that mean it’s a useless fetish object for the bourgeoisie? Artists are the first to admit that if there was a choice between funding a hospital or an art museum, we'd all choose the hospital... but... what if art could save lives? HELP (Is anyone an artist?) is a mobile performance which will explore what it looks like when art tries to save a life.

The performance will begin at 6pm on the sidewalk in front of Genthiner Str. 36 (look for the project space festival poster) and proceed (pretty quickly) along the route shown below. Afterwards all are welcome to join us for a späti drink near the end of the route.

Come by, help us (hey are you an artist?)

photos by Piotr Pietrus

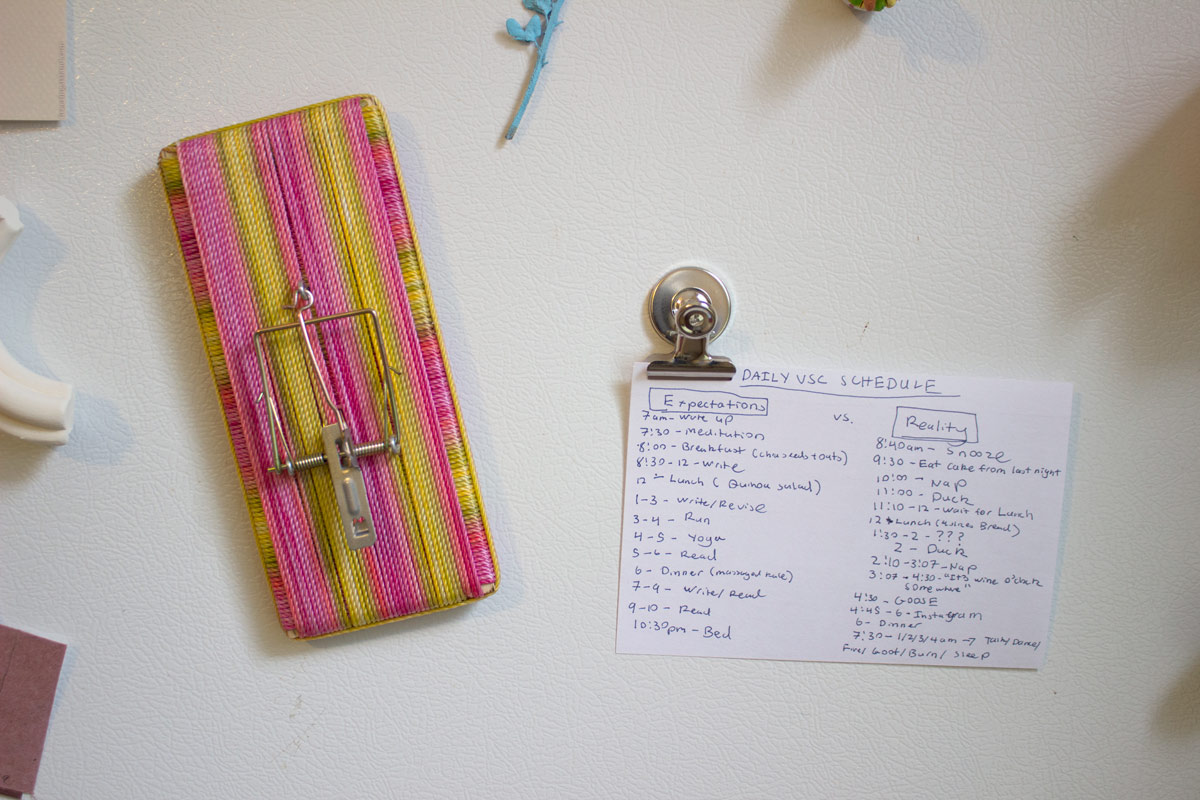

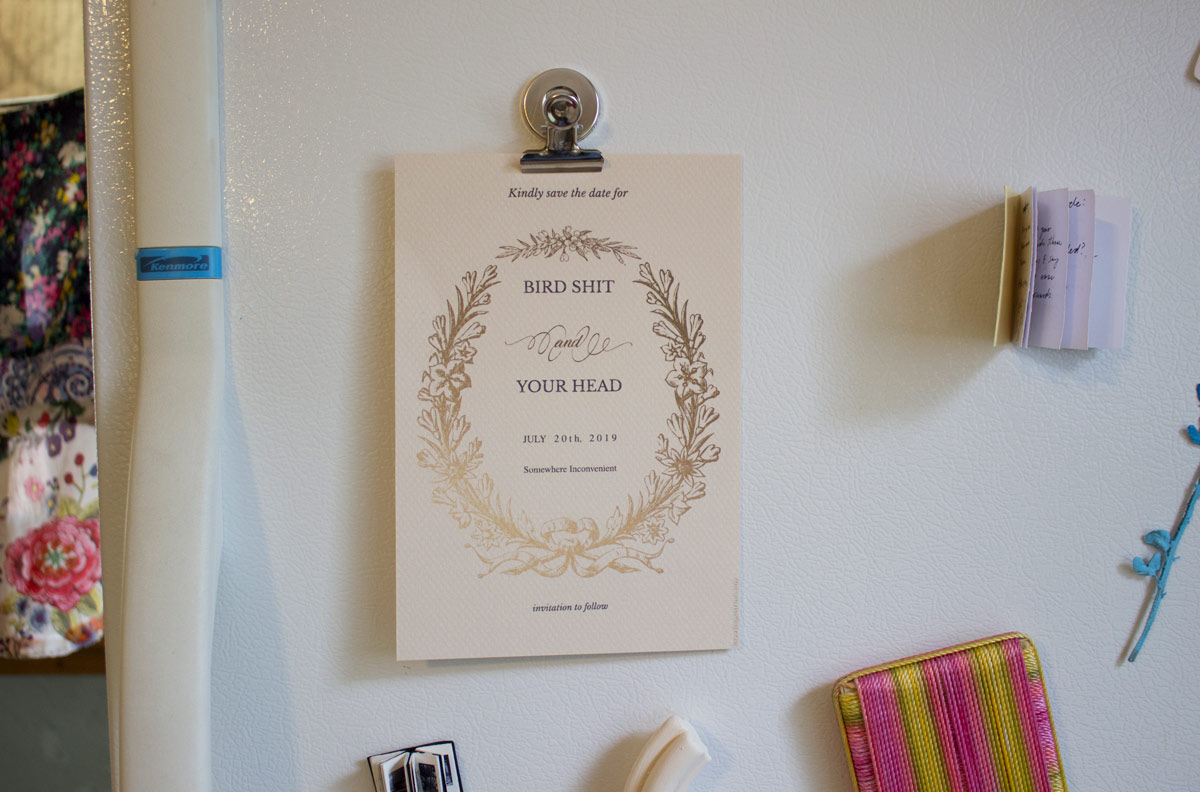

Fridge Show

opening April 25th, 7-10pm

@ Diney House

Lower Main Str. W

05656 Johnson, Vermont

I was never very good at art

I shunned the macaroni

pasted in a clumsy heart

I felt myself a phony

I could never get the hang of wood

It’s heavy and I’m weak

nothing in pine was any good

let alone in teak

my paintings sag, their stretcher bars

pulled down by indecision

no publisher wants my memoirs

they say I lack ‘a vision’

the Guggenheim don’t want me

and the Biennale said they’ll pass

I won’t be on the Cannes marquee

I haven’t got the class

but I remember one sweet morn

before her game of bridge

my mother took my work, half torn

and hung it on the fridge.

Organized by Annelies Kamen for Crybaby

with

Stephanie Adams-Santos • William Beattie • Elizabeth Bisbing • Julia Bosson • Conrad Cheung • Dexter Ciprian • Sarah Fox • Alice Foxen • Morgan Rose Free • Amanda Galvan Huynh • Brynda Glazier • Lori Goldberg • Jessalyn Haggenjos • H. A. Halpert • Marielle Hehir • Lorraine Heller-Nicholas • Candace Jensen • Sun Young Kang • Nolan Lem • Jessy Lu • Rachel Macfarlane • Kenny Nguyen • Olimpia Piccoli • Madeleine Preston • Ron Prigat • Yoshie Sakai • Tiffany Jaeyeon Shin • Kelsey Shwetz • Alyssa Songsiridej • Mike Soto • Julia Thomson • Laura Waller • Yi Ting Wang • Daniel Zeese

Ain’t No Use

opening March 22nd, 6-10pm

and March 23rd by appointment

@ Crybaby

Genthiner Str. 36

10785 Berlin

crybabyberlin@gmail.com

“Rather like wishing to hammer a table together tidily, meticulously, with a craftsman's skill, and at the same time do nothing. But not so that they could say: 'Hammering is nothing to him,' but rather 'Hammering is real hammering to him, and at the same time it is nothing too,' which would of course make the hammering become even bolder, even more resolute, even more real, and, if you like, more crazy."

The exhibition ‚Ain’t No Use’ presents a collection of works that engage with the question of utility - inverting the attributes of functionality and through modification or commentary relating to their surrounding environment.

/

»einen Tisch mit peinlich ordentlicher Handwerksmäßigkeit zusammenzuhämmern und dabei gleichzeitig nichts zu tun und zwar nicht so, daß man sagen könnte: >Ihm ist das Hämmern ein Nichts<, sondern >Ihm ist das Hämmern ein wirkliches Hämmern und gleichzeitig auch ein Nichts<, wodurch ja das Hämmern noch kühner, noch entschlossener, noch wirklicher und, wenn du willst, noch irrsinniger geworden wäre.«

Die Ausstellung „Ain’t No Use“ versammelt Arbeiten, die sich mit der Frage nach Nutzbarkeit auseinandersetzen, Funktionszuschreibungen umkehren und sich mal modifizierend, mal kommentierend auf den sie umgebenden Raum beziehen.

with

Lotta Bartoschewski

Olga Jakob

Dargelos Kersten

John Schulz

Erin Woodbrey

organized by Samantha Bohatsch & Annelies Kamen

Installation Views

photos by Philippe Gerlach

The exhibition Ain’t No Use presents a collection of works that engage with the question of utility - invert- ing the attributes of functionality and through modification or commentary relating to their surrounding environment.

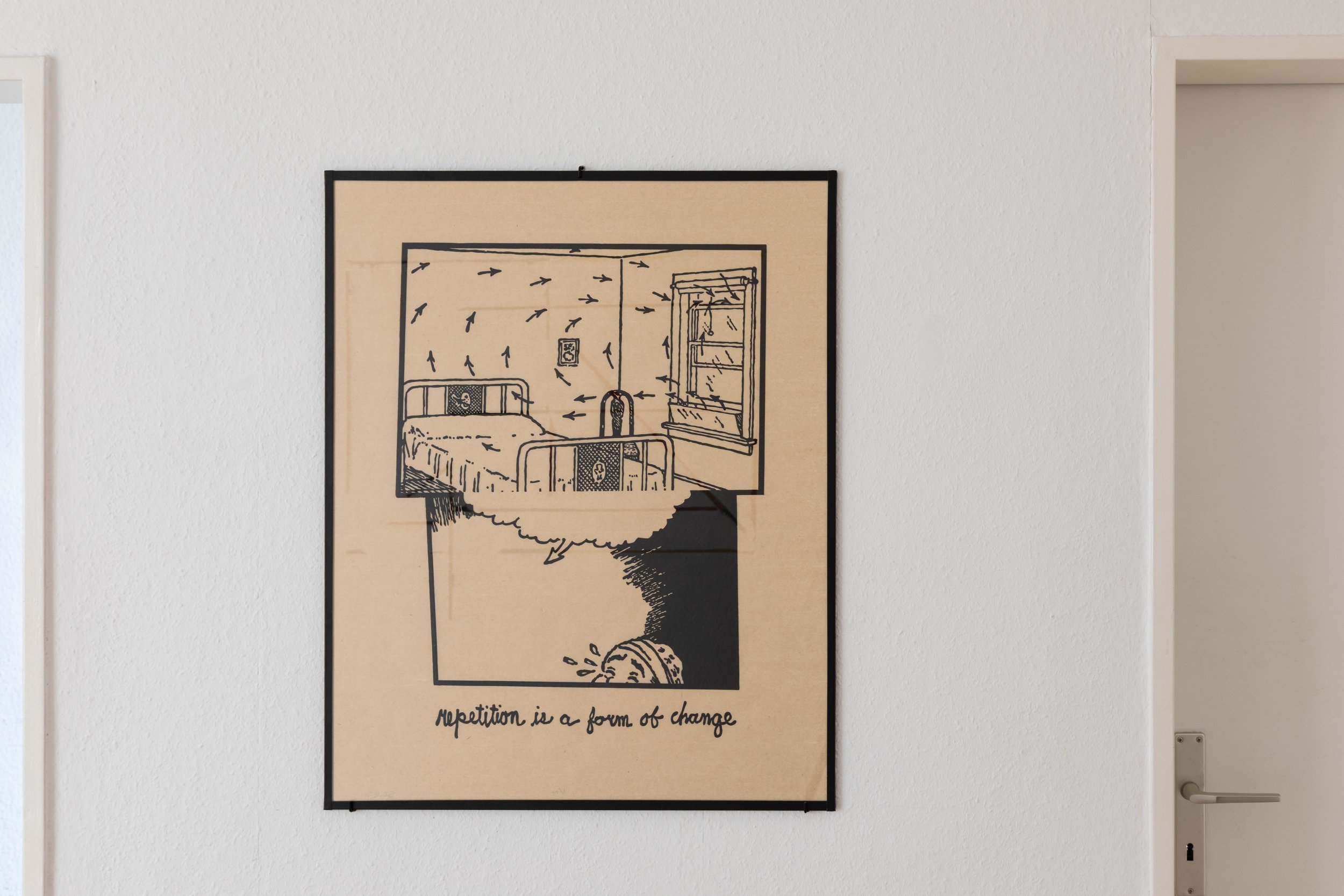

John Schulz’s woodcut print, strategies (repetition is a form of change) (2010) acts as the jumping-off point for the exhibition, taking on the role of a prologue. The arrows, which in the image stretch through the window into the room and circle back out, indicate a constant cycling through which – according to the subtitle– change is created. Ain’t No Use assumes this concept of exchange: The space, the works on show and the various perspectives of the viewers yield a system of reciprocal influence.

Clearly, the exhibition space is not a white cube expressly conceived to display art, but rather an apartment that has been temporarily repurposed. What does this mean for the perception of the works? Does the room with- draw and cede itself to the artworks or does it assert its own function as a private living space?

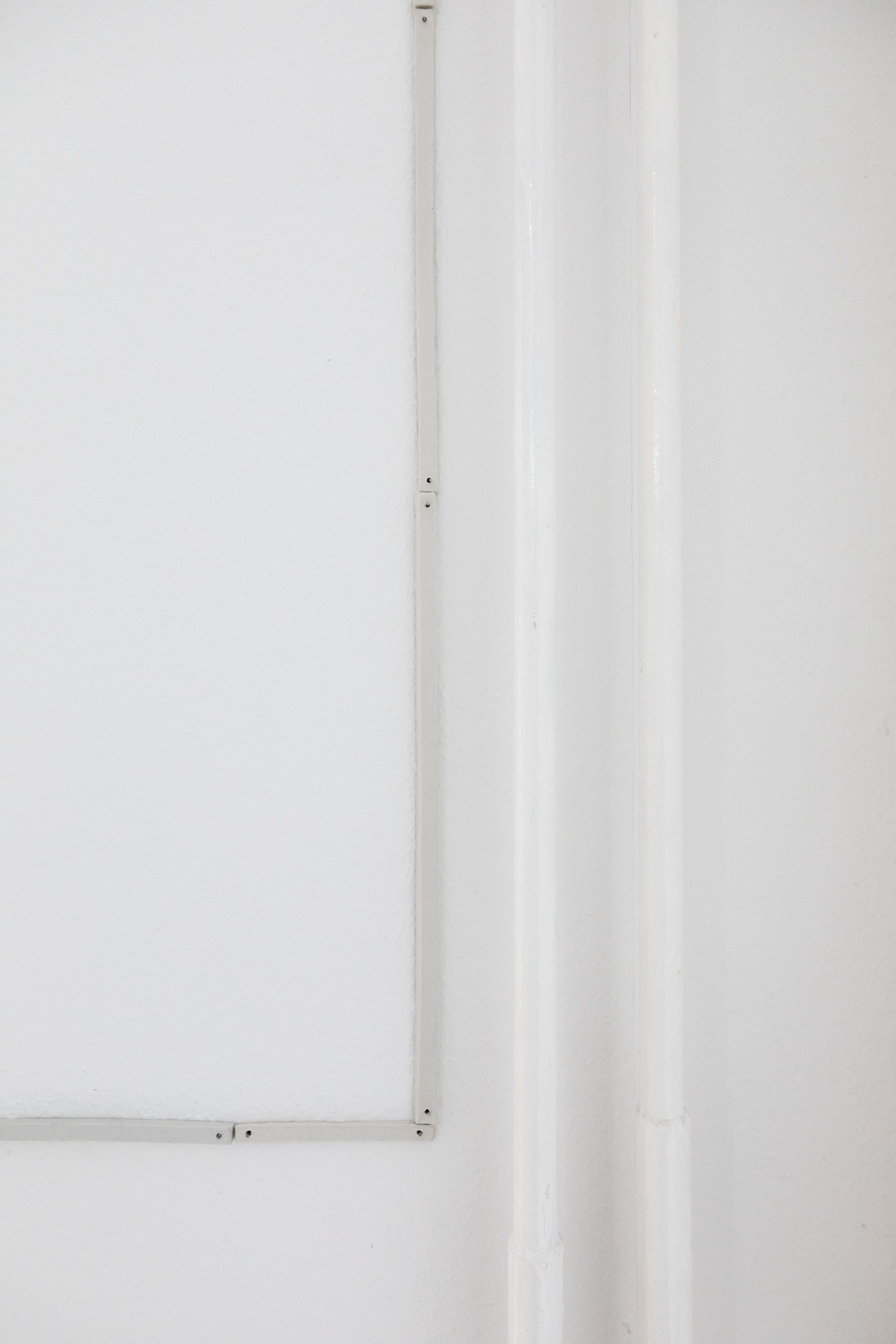

At first glance Erin Woodbrey’s Raum (2019) is reminiscent of a cable conduit: while the narrow line mostly follows the assumed cable channels along the skirting board, near the window it appears that it was rerouted, perhaps to avoid a piece of furniture. Is a former state of the room visible here? Upon closer inspection, it be- comes clear that this work is not made of plastic, but rather porcelain rods in various lengths, attached to the wall with nails. The precious material, also called white gold, stands in stark contrast to the first presumption. What remains however, is the impression that it in- scribes an imaginary room into the existing space. In its reduced formal language Raum is reserved and subtle, but nevertheless transformative to its environment.

In Untitled (2019), Woodbrey hearkens back to industrially produced construction elements. Like a remnant or forgotten leftover, the drywall module leans against the wall of the space. Originally designed to contain a space, it is now functionless outside of itself and placed in the context of art. The object points to its environment and its own original unfulfilled function. Dargelos Kersten’s work Bench (2014) also plays with the attributes of function as well as with the associated behavior of visitors. If the bench is categorized as a piece of furniture, it invites you to have a seat. If it is

perceived not as seating, but rather as an art object in the form of a bench, further considerations arise: to sit or not to sit? And particularly: does the rule of the art context apply, to maintain a certain distance from the work, or does the work adjust itself to the function of a bench, an object of utility?

As if to push this game to its logical limits, in Bad-Silicon (2019) Kersten wholly nullifies the distinction between functional and art objects. This work, installed in the bathroom in-situ and integrated into its environment, fulfills its function as a waterproof seal. Simultaneously, its color sets itself apart from the rest of the silicone joints and refers to its special status as an artwork.

The sculpture Breaking News (2019) by Lotta Bartoschewski engages with the most distinctive characteristic of the room, the rounded niche, which sparks thoughts about its possible original function. Pre-war apartments, built in an epoch that demanded different requirements from living space, often have such spaces whose original function and meaning are not immediately accessible. These residues are hints of another time and another way of living. The newspaper articles and ink integrated into the plaster of Breaking News produce a pattern that suggests that in their arrangement, some secrets of the room are perceptible.

Olga Jakob’s textile work Kufi (2017) evokes an architectural frieze. The patterns that run the length of the fabric look like the marks from an ornament that no longer exists in its original form. While a frieze is meant to structure and decorate architecture, literally carved in stone into place, Kufi fundamentally differentiates itself from this role. The light fabric that can at any moment be removed, repositioned or placed somewhere entirely new, stands in stark contrast to the materiality and function of the architectural element that it references.

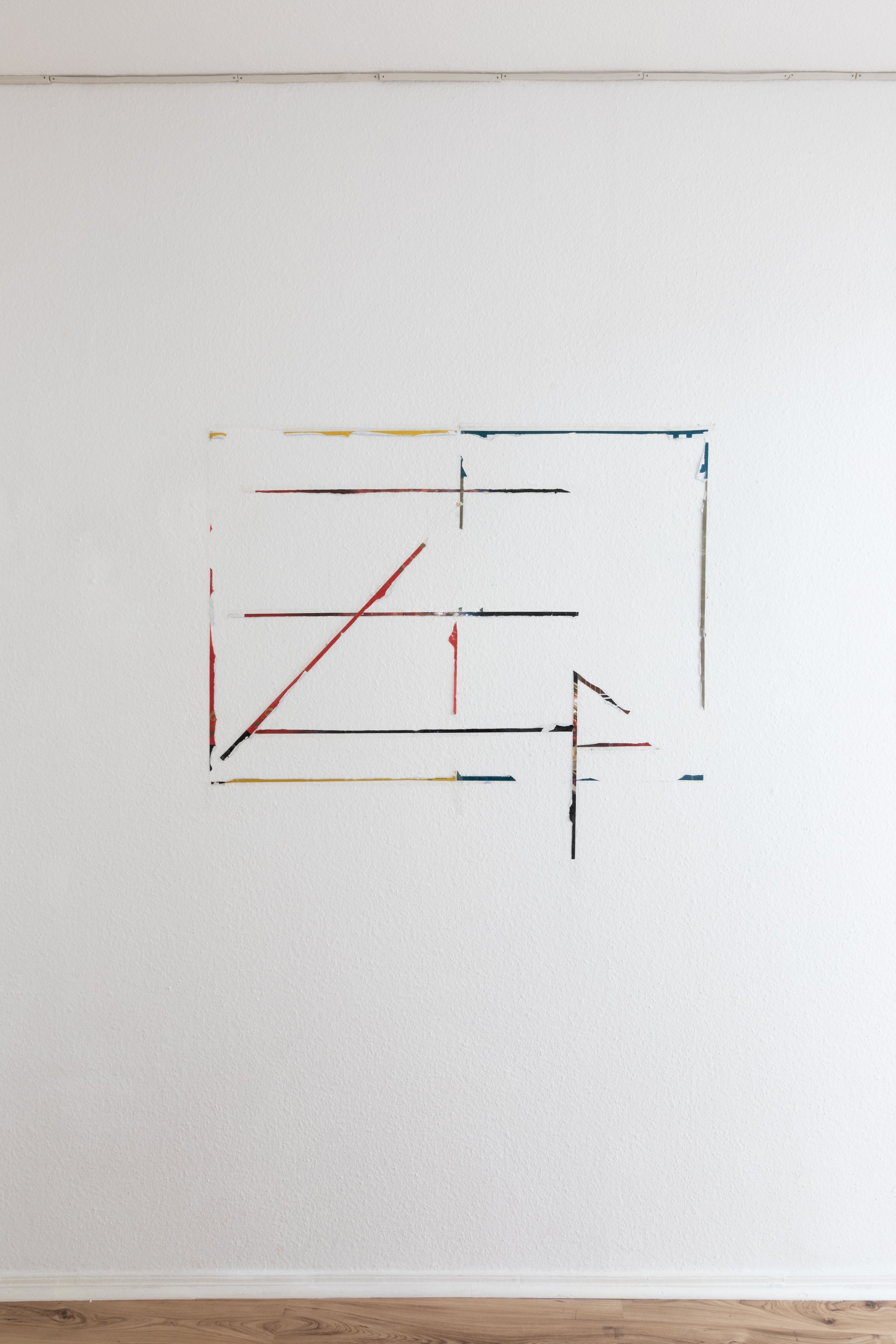

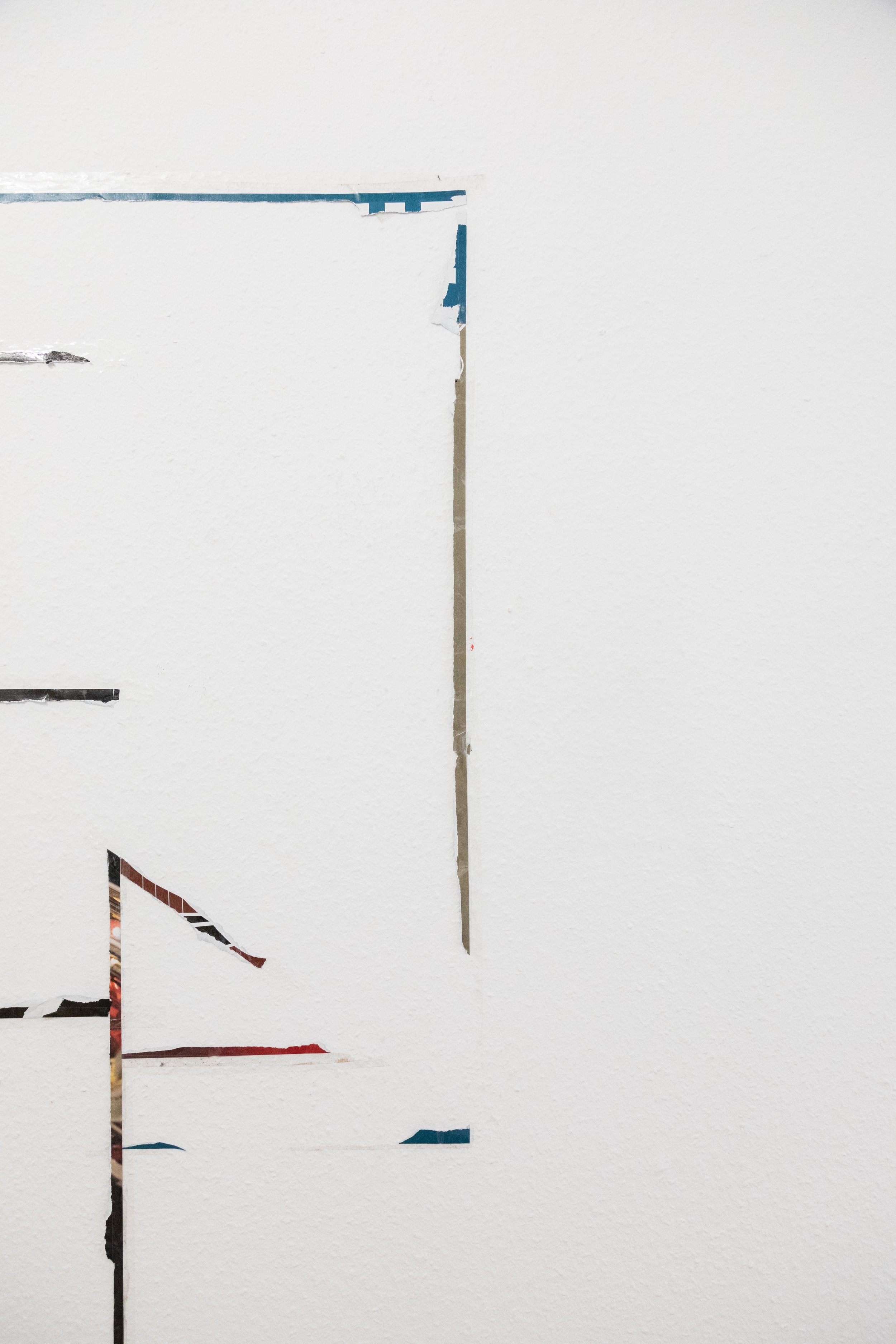

In Jakob’s ohne Titel (2019), leftovers from posters taped to the wall form a wall drawing. The source material is nearly completely removed, only minimal remnants remain, becoming the origin point for new forms.

Text by Ferial Nadja Karrasch

Translation by Annelies Kamen

/

Die Ausstellung Ain’t No Use versammelt Arbeiten, die sich mit der Frage nach Nutzbarkeit auseinandersetzen, Funktionszuschreibungen umkehren und sich mal modifizierend, mal kommentierend auf den sie umgebenden Raum beziehen.

John Schulz’ Holzschnitt strategies (repetition is a form of change) (2010) bildet den Ausgangspunkt der Ausstellung und nimmt die Rolle eines Prologs ein. Die durch das Fen- ster in das Zimmer gelangenden und so auch wieder nach draußen führenden Pfeile deuten einen permanenten Kreislauf an, durch den – so der Text unterhalb des Motivs – Veränderung erzeugt wird. Diese Idee des Austauschs wird in Ain’t No Use übernommen: Der Raum, die gezeigten Arbeiten und die unterschiedlichen Rezeptionsweisen der Besuchenden ergeben ein Gefüge wechselseitiger Einflussnahme.

Es ist hierbei offensichtlich, dass es sich bei dem Ort der Ausstellung nicht um einen eigens für Kunst konzipier- ten White Cube handelt, sondern um eine Wohnung, die zeitweise umfunktioniert wurde. Was bedeutet dies für die Wahrnehmung der ausgestellten Werke? Nimmt der Raum sich weitestgehend zurück und überlässt den Kunstwerken das Feld oder behauptet er seine eigene Funktion als privaten Ort des Wohnens?

Auf den ersten, flüchtigen Blick erinnert Erin Woodbreys Raum (2019) an den Verlauf einer Kabelabdeckung: Während die schmalen Linien des vermeintlichen Kabelkanals zum größten Teil entlang der Scheuerleisten verlaufen, scheinen sie in der Nähe des Fensters um ein Möbel herum verlegt worden zu sein. Wird hier etwa ein früherer Zustand des Zimmers sichtbar? Aus der Nähe betrachtet wird deutlich, dass es sich nicht um Kunststoff handelt, sondern um unterschiedlich lange Porzellanstücke, die mithilfe von Nägeln an der Wand befestigt wurden. Das edle Material, auch Weißes Gold genannt, steht in starkem Kontrast zu der ersten Vermutung. Was allerdings bleibt, ist der Eindruck, dass sich ein imaginärer Raum in den tatsächlichen einschreibt. In ihrer reduzierten Formensprache ist Raum zurückhaltend und subtil, während sie sich gleichzeitig verändernd auf ihre Umgebung auswirkt.

In Untitled (2019) greift Woodbrey auf ein industriell gefertigtes Bauelement zurück: Wie ein übrig gebliebenes oder vergessenes Überbleibsel lehnt das Trockenbaumodul an der Zimmerwand. Ursprünglich dafür gedacht, einen Raum abzugrenzen, hat es nun keine Funktion mehr außerhalb seiner selbst und wird in eine Art Referenzbeziehung gestellt: Das Objekt verweist auf seine Umgebung und auf den eigenen ursprünglichen Zweck ohne diesen jedoch zu erfüllen.

Dargelos Kerstens Arbeit Bench (2014) spielt ebenfalls mit Funktionszuschreibungen und den damit verbundenen Verhaltensweisen der Benutzer*innen bzw. Rezipient*innen. Wird die Bank als Möbel kategorisiert, mag sie dazu einladen, sich hinzusetzen. Wird sie jedoch nicht primär als Sitzgelegenheit sondern vielmehr als Kunstgegenstand in Gestalt einer Bank wahrgenommen, resultiert dies vermutlich in weiteren Überlegungen: Hinsetzen oder nicht Hinsetzen? Und vor allem: Gilt hier das Abstands-Gebot oder passt sich das Werk der eigentlichen Funktion des Gebrauchsgegenstands „Bank“ an?

Wie um dieses Spiel an seine Grenzen zu treiben, hebt Kersten in Bad-Silicon (2019) den Unterschied zwischen funktionalem und Kunst-Objekt schließlich vollständig auf. Die im Badezimmer installierte in situ-Arbeit integriert sich in ihre Umgebung und erfüllt ihren Dienst als Schutz vor dem Wasser. Gleichzeitig hebt sie sich aufgrund der unterschiedlichen Farbigkeit eindeutig von den restlichen Verfugungen ab und verweist so auf ihren Sonderstatus als Kunstwerk.

Die Skulptur Breaking News (2019) von Lotta Bartoschewski bezieht sich auf das markanteste Charakteristikum des Raumes: Die gerundete Nische, die zu Überlegungen anregt, welche Funktion ihr ursprünglich zukam. Altbauwohnungen, erbaut in einer Epoche, die andere Anforderungen an einen Wohnort stellten, haben es oft an sich, Elemente zu enthalten, deren ursprüngliche Bedeutung sich heute nicht umgehend erschließt. Diese Rückstände werden so zu Spuren einer anderen Zeit und einer anderen Art des Wohnens. Die in Breaking News in den Gipsabdruck integrierten Zeitungsartikel und die Tusche ergeben ein Muster, das den Eindruck erweckt, in dieser Anordnung ließe sich etwas Geheimnisvolles über den Raum erfahren.

Olga Jakobs Stoffarbeit Kufi (2017) ruft Assoziationen zu einem Fries hervor: Das über die lange Stoffbahn verlaufende Muster erscheint wie der verbleibende Rest eines Ornaments, das längst nicht mehr in seiner ursprünglichen Form vorhanden ist. Während ein Fries in der Architektur darauf abzielt, eine Fassade zu gliedern oder zu schmücken und buchstäblich in Stein gemeißelt ist, unterscheidet sich Kufi hiervon grundlegend. Der leichte Stoff, der jederzeit abgenommen und an anderer Stelle wieder angebracht werden kann, steht in starkem Kontrast zu der Materialität und Funktion des architektonischen Stilelements.

In Jakobs ohne Titel (2019) bilden die Rückstände eines an die Wand geklebten Posters eine Art Wandzeichnung. Das Ausgangsmaterial wird weitestgehend entfernt, es wird noch ein minimaler Rest erhalten, der den Ausgangspunkt einer neuen Form ergibt.

Text von Ferial Nadja Karrasch